The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter

1902

Illustrated by Beatrix Potter

With characters named Jemima Puddle-duck and Mrs. Tiggy-winkle, you might think that Beatrix Potter’s tales are fluff and whimsy. But if you read the 23 little volumes in the boxed set, you will find surprising sophistication and subtle wit. There is a dense richness – of language, of nuance, of humor. Beatrix Potter wrote with a no-nonsense matter-of-fact edge, for she was familiar enough with the natural world to realize that lyrical romanticism is hardly the apposite tone. The animals in her world are very aware of their position in the food chain. Peter Rabbit’s father ended up in Mr. McGregor’s meat pie. The foxhounds, after saving the clueless Jemima Puddle-duck from the wily fox, proceed to gobble down her eggs. Squirrel Nutkin lays three dead mice (a shocking image) at the foot of the old owl as a propitiatory offering in exchange for nuts. The stories are rich because Beatrix Potter, like the best of children’s authors, understood that children are not really as sentimental as some might hope.

The Tale of Peter Rabbit, her masterpiece, is a perfect story. It is an allegorical tale of the explorations of childhood, with Mr. McGregor’s garden being the delicious and dangerous world that any spirited bunny would want to experience. The story is beautifully balanced with its rise and fall structure, beginning and ending with the quiet comfort of home and mother. In between, Peter Rabbit experiences the pleasures of the forbidden feast, the fright of the chase, the despair of isolation. There is beautiful pairing of text and illustration, as can only happen when writer and artist are one and the same. What could better convey Peter Rabbit’s aloneness than the delicate image of a forlorn shoe lost among the cabbages? Where has a child’s desolation been better portrayed than in the picture of Peter Rabbit leaning against the locked garden door, one foot resting on the other, a single tear falling?

Beatrix Potter’s exquisite watercolor illustrations convey the artist’s deep understanding of the natural world. Her appreciation began as a child – raised by governesses, sheltered from other children, she observed and sketched her menagerie of animals who would  later people her stories. As a young adult, she developed a passionate interest in mycology and her botanical illustrations of fungi and lichens were highly regarded by other naturalists. In her children’s books, her illustrations of animal characters have become iconic, but her tree trunks, leaves, rocks, and dirt are as beautifully rendered as her velvety soft bunnies.

later people her stories. As a young adult, she developed a passionate interest in mycology and her botanical illustrations of fungi and lichens were highly regarded by other naturalists. In her children’s books, her illustrations of animal characters have become iconic, but her tree trunks, leaves, rocks, and dirt are as beautifully rendered as her velvety soft bunnies.

Aside: The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies, one of several  stories set in Mr. McGregor’s garden, begins with an imaginative premise: “It is said that the effect of eating too much lettuce is ‘soporific’”.

stories set in Mr. McGregor’s garden, begins with an imaginative premise: “It is said that the effect of eating too much lettuce is ‘soporific’”.

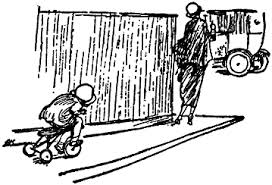

Disobedience is one of A.A. Milne’s most memorizable poems, and one of his best. He portrays the wonderful independence of a child’s mind and the natural audacity – James James goes immediately to the royals for help, in this case King John. Children reading the poem delight in the conceit – for children who are rarely in charge, it is a welcome relief to enter a world in which the mother is leashed to the tricycle rather than vice versa, and the mother is guilty of disobedience and suffers the consequences. It is a sign of Milne’s respect for children that there is no happy resolution – the mother is gone, for good. James James is not particularly sad about his loss, but simply disappointed that his mother failed to listen to him.

Disobedience is one of A.A. Milne’s most memorizable poems, and one of his best. He portrays the wonderful independence of a child’s mind and the natural audacity – James James goes immediately to the royals for help, in this case King John. Children reading the poem delight in the conceit – for children who are rarely in charge, it is a welcome relief to enter a world in which the mother is leashed to the tricycle rather than vice versa, and the mother is guilty of disobedience and suffers the consequences. It is a sign of Milne’s respect for children that there is no happy resolution – the mother is gone, for good. James James is not particularly sad about his loss, but simply disappointed that his mother failed to listen to him.