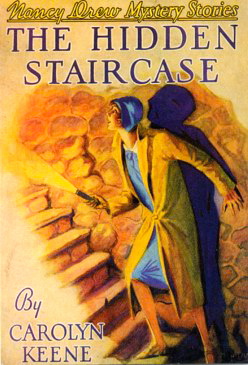

The Hidden Staircase by Carolyn Keene

1930

Illustrated by Russell Tandy

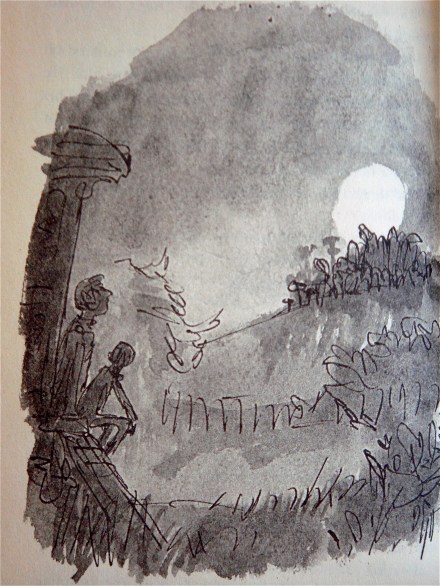

For anyone who has read the original editions of the early Nancy Drew mysteries, the lasting memory is of painful suspense. Nancy Drew, alone at home at night, opens the door to a malevolent villain who threatens her with violence. On a stormy eve, she breaks into her enemy’s sinister house; the cellar window bangs shut behind her, alerting the surly housekeeper who comes to investigate. Locked in an upstairs bedroom, she finds the opening to the hidden underground passage, whose length she traverses with a flickering flashlight (that eventually fails), uncertain if she will encounter her nemesis in the rat-infested depths. The ancient mansion in which she is staying has no phone and Nancy keeps her dangerous plans to herself, so there is a dread sense of isolation.

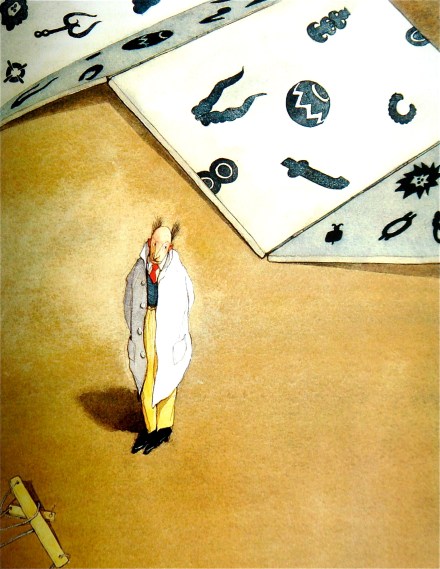

These scenes are from The Hidden Staircase, the second in the series. There is a raw energy that is startling, beginning with the appearance of Nathan Gombet, tall and spindly like a “towering scarecrow”, with piercing eyes that repulse the young woman. There is a Silence of the Lambs sinister quality to this character. When Nancy happens into the room filled with his menacing taxidermied bird specimens (Hitchcock bestowed the same hobby on Norman Bates) along with live canaries in gilded cages, the sense of a deranged unpredictably violent character is complete. There are the gothic atmospherics, from the architecture to the weather (always stormy, always night), and the queer happenings intended to frighten the elderly sisters into selling their family home – an infestation of flies, shadow figures on the walls, the disappearance of three black silk dresses.

These touches came from the imagination of Mildred Wirt Benson, a woman from Iowa who was hired by the Stratemeyer Syndicate (creators of the Hardy Boys and the Bobbsey Twins, among many others) to ghostwrite the Nancy Drew mysteries under the pseudonym of Carolyn Keene: she received $125 per volume in exchange for a vow of silence. She wrote most of the volumes published from 1930 to 1953, but her role remained hidden until she testified in a court case between publishing houses in 1980. Edward Stratemeyer created the series, but Benson gave life to the character who was to fire the imagination of generations of girls – the attractive blond amateur sleuth in her blue roadster, seeking justice for the downtrodden with her chums, Bess and George, and her endlessly patient beau, Ned Nickerson. The early Nancy Drew is feisty, courageous, determined, outspoken, capable, and invincible, and it is worth seeking her out. In 1959, she underwent a transformation as the original volumes were condensed and rewritten. The revised version of The Hidden Staircase, which is the yellow-spined volume found in most book stores and libraries, is pallid, spiceless, and two-dimensional. Gone is the colorful accomplice: “’You git, white man!’ she ordered, ‘or I’ll fill yo’ system full of lead.’” Gone is the incompetent sheriff who inspires Nancy’s sarcastic disdain. Gone is the frightening villain, replaced by a short stooped man who has no interest in taxidermy. And because Nancy Drew is no longer alone at moments of danger, gone is the suspense.

These touches came from the imagination of Mildred Wirt Benson, a woman from Iowa who was hired by the Stratemeyer Syndicate (creators of the Hardy Boys and the Bobbsey Twins, among many others) to ghostwrite the Nancy Drew mysteries under the pseudonym of Carolyn Keene: she received $125 per volume in exchange for a vow of silence. She wrote most of the volumes published from 1930 to 1953, but her role remained hidden until she testified in a court case between publishing houses in 1980. Edward Stratemeyer created the series, but Benson gave life to the character who was to fire the imagination of generations of girls – the attractive blond amateur sleuth in her blue roadster, seeking justice for the downtrodden with her chums, Bess and George, and her endlessly patient beau, Ned Nickerson. The early Nancy Drew is feisty, courageous, determined, outspoken, capable, and invincible, and it is worth seeking her out. In 1959, she underwent a transformation as the original volumes were condensed and rewritten. The revised version of The Hidden Staircase, which is the yellow-spined volume found in most book stores and libraries, is pallid, spiceless, and two-dimensional. Gone is the colorful accomplice: “’You git, white man!’ she ordered, ‘or I’ll fill yo’ system full of lead.’” Gone is the incompetent sheriff who inspires Nancy’s sarcastic disdain. Gone is the frightening villain, replaced by a short stooped man who has no interest in taxidermy. And because Nancy Drew is no longer alone at moments of danger, gone is the suspense.

The Hidden Staircase was Mildred Wirt Benson’s favorite. Facsimile editions that reproduce the original 1930 volume are available, as are countless pre-1959 used copies.