The Selkie Girl by Susan Cooper

The Selkie Girl by Susan Cooper

1986

Illustrated by Warwick Hutton

In the legends of the seafaring peoples of northern Scotland and Ireland, the seal is a shapeshifter. According to Orkney legend, selkies are fallen angels: those who fall on land become fairies and those who fall on the sea become seals, and so they must remain until Judgement Day. Once every seven years (or, according to some, once a year), the seal can be transformed into human form and walk on land. The male selkie seeks out lonely unsatisfied women who welcome his amorous advances. The female selkie becomes an unwilling captive bride and pines for the sea.

The Selkie Girl tells the Orkney legend of the female seal, lyrically written by the English author, Susan Cooper. Donallan is a fisherman who lives in an island croft (farmhouse), alone save for his dog, Angus, and his cat, Cat. He falls in love with a beautiful selkie and steals her sealskin so that she cannot resume her animal form. They marry and have children, but she is forever staring sadly out to sea. The youngest child, unaware of its significance, tells his mother the whereabouts of the sealskin his father has kept carefully hidden. The selkie takes leave of her two youngest children (her three oldest are at work in the fields) and slips into the sea. As a seal, she provides Donallan with safe passage during storms, and once a year she becomes a woman and visits her husband and children.

The Selkie Girl tells the Orkney legend of the female seal, lyrically written by the English author, Susan Cooper. Donallan is a fisherman who lives in an island croft (farmhouse), alone save for his dog, Angus, and his cat, Cat. He falls in love with a beautiful selkie and steals her sealskin so that she cannot resume her animal form. They marry and have children, but she is forever staring sadly out to sea. The youngest child, unaware of its significance, tells his mother the whereabouts of the sealskin his father has kept carefully hidden. The selkie takes leave of her two youngest children (her three oldest are at work in the fields) and slips into the sea. As a seal, she provides Donallan with safe passage during storms, and once a year she becomes a woman and visits her husband and children.

The poignancy of the story is unusual among children’s books, but it is not overdone. The selkie explains, “I have five children in the sea and five on the land. And that is a hard case to be in.” Her daughter responds simply. “You must go to them. It’s their turn…. I’ll look after James.”

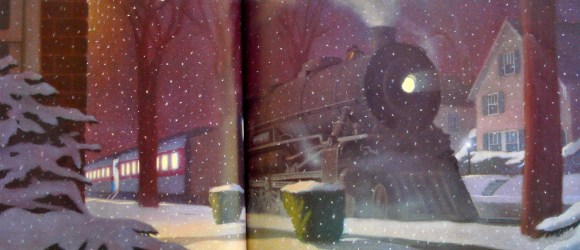

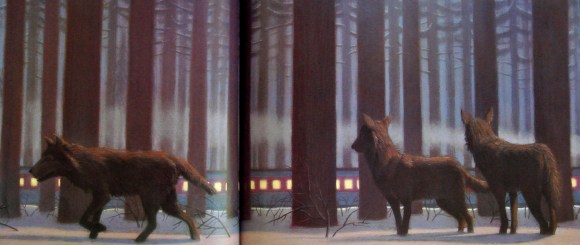

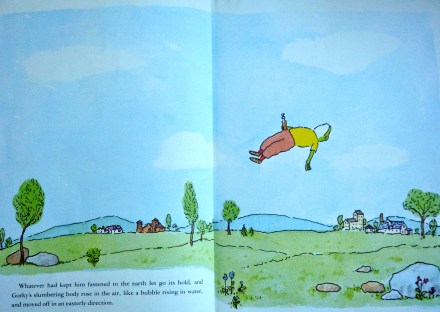

Susan Cooper imbues a sad timelessness to the tale with the simplicity of her language. Warwick Hutton achieves a matching tone with his quiet watercolors. His figures are static, yet never lifeless: each picture has the appearance of a posed set piece, arranged by the hands of fate. The Selkie Girl is one in a series of three Celtic tales, the others being The Silver Cow and Tam Lin.

Susan Cooper imbues a sad timelessness to the tale with the simplicity of her language. Warwick Hutton achieves a matching tone with his quiet watercolors. His figures are static, yet never lifeless: each picture has the appearance of a posed set piece, arranged by the hands of fate. The Selkie Girl is one in a series of three Celtic tales, the others being The Silver Cow and Tam Lin.

Aside: In the mythology of the Amazon River basin, it is the pink Amazon River dolphin who is the shapeshifter. At night, he emerges from the water as a handsome Don Juan, dressed stylishly in white, and seduces beautiful girls at the village dance. As dawn approaches, the encantado slips away to his enchanted river world, sometimes with his lover in tow.