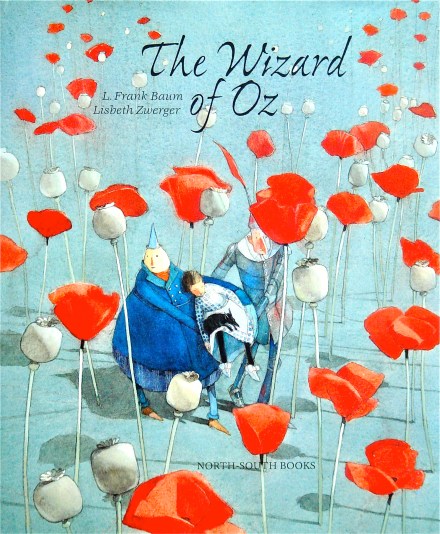

The Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

1900

Illustrated by Lisbeth Zwerger

Of the many beloved children’s books, none has been more embraced by American popular culture than The Wizard of Oz. Originally published in 1900, the book’s phenomenal success launched a slew of sequels, prompted Hollywood to create one of the most-viewed movies of all time, and inspired a number of wildly popular Broadway musicals. The yellow brick road, the ruby slippers (silver in the book), the Wicked Witch of the West, Judy Garland singing the impossibly beautiful Over the Rainbow – these are all familiar and enduring icons in the American vernacular. In reading the book today, it is startling how fresh and modern it feels. There is nothing old-fashioned or nostalgic that would suggest that it was written over a century ago.

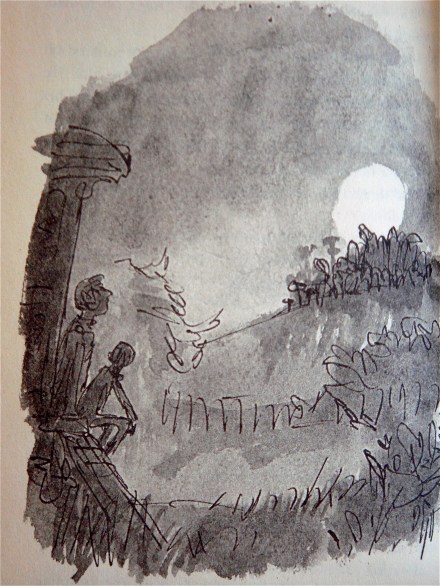

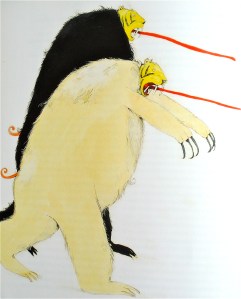

L. Frank Baum was an impresario of sorts who threw himself into a bewildering sequence of professions, most without great success. He finally discovered his genius as a storyteller. His imaginative universe was fresh and light – revolutionary qualities in a genre that was dominated by the dark, Germanic, and moralistic. He combined Midwestern realism (Kansas tornado, talking scarecrow) with old-world fairy tale elements (evil witches, protective kisses), a phantasmagoria of bizarre hallucinogenic characters (blue Munchkins, Winged Monkeys, armless Hammer-Heads) with optimistic 20th century psychology to create a unique species of magic.

L. Frank Baum was an impresario of sorts who threw himself into a bewildering sequence of professions, most without great success. He finally discovered his genius as a storyteller. His imaginative universe was fresh and light – revolutionary qualities in a genre that was dominated by the dark, Germanic, and moralistic. He combined Midwestern realism (Kansas tornado, talking scarecrow) with old-world fairy tale elements (evil witches, protective kisses), a phantasmagoria of bizarre hallucinogenic characters (blue Munchkins, Winged Monkeys, armless Hammer-Heads) with optimistic 20th century psychology to create a unique species of magic.

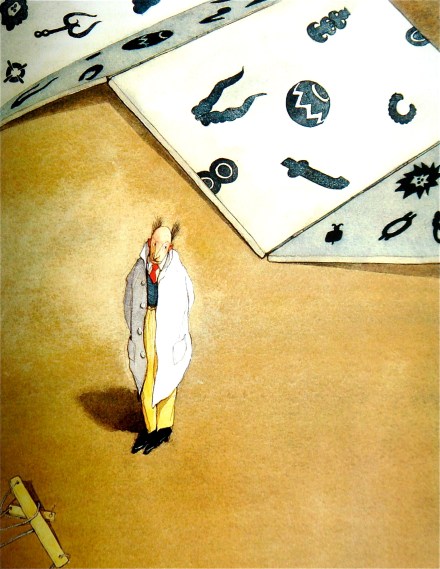

Dorothy and her three companions, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Lion, take center stage in their quests for home, intelligence, heart, and courage. But Baum’s most original and complex creation was the Wizard. Stripped of his disguises, he turns out to be a meek and humble charlatan who is the victim of the world’s desire to be fooled. “How can I help being a humbug,” he said, “when all these people make me do things that everybody knows can’t be done?” Witness the willingness of the three seekers to suspend their disbelief long enough to acquire their missing qualities. It should be noted that Baum had become a Theosophist only a few years before writing his first Oz book, and he cannot have been unaware of the charges of fakery leveled against Madame Blavatsky when she caused teacups to materialize and tables to levitate.

Of the many illustrators of The Wizard of Oz, Lisbeth Zwerger best captured the character of the humbug. She draws him as an awkward perplexed mad scientist with wings of wired hair framing his bald pate. His vulnerability and his chagrin at having been exposed as a conjuror are apparent. Zwerger also does justice to the bizarreness and surrreality of Baum’s imagination – perhaps Dorothy was not the only one to be overcome by the fragrance of the red poppies. To complete the experience, a pair of emerald-green tinted glasses, the cardboard decorated with occult sorcerer symbols, is secreted in the back of Zwerger’s editions, to be slipped on when Dorothy and her friends arrive at the Emerald City.

Of the many illustrators of The Wizard of Oz, Lisbeth Zwerger best captured the character of the humbug. She draws him as an awkward perplexed mad scientist with wings of wired hair framing his bald pate. His vulnerability and his chagrin at having been exposed as a conjuror are apparent. Zwerger also does justice to the bizarreness and surrreality of Baum’s imagination – perhaps Dorothy was not the only one to be overcome by the fragrance of the red poppies. To complete the experience, a pair of emerald-green tinted glasses, the cardboard decorated with occult sorcerer symbols, is secreted in the back of Zwerger’s editions, to be slipped on when Dorothy and her friends arrive at the Emerald City.