A Stranger at Green Knowe by Lucy Boston

A Stranger at Green Knowe by Lucy Boston

1961

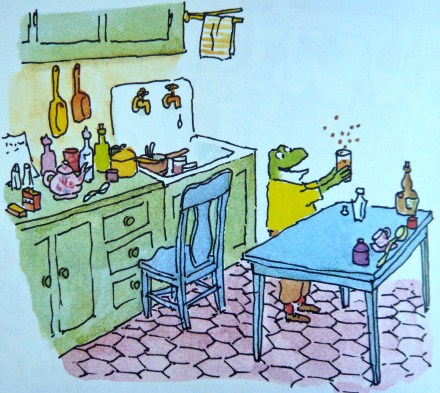

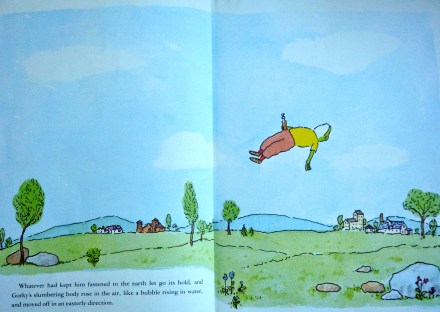

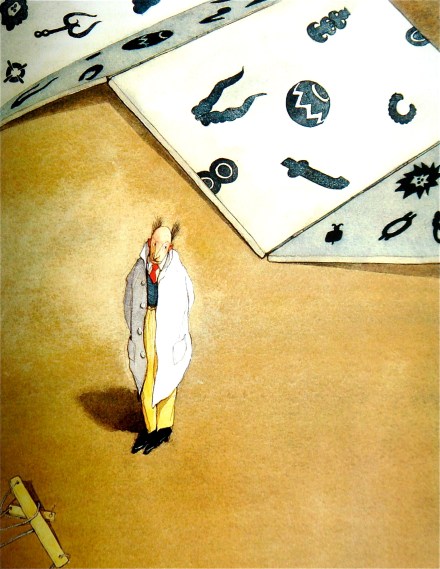

Illustrated by Peter Boston

Of the six books that comprise the Green Knowe chronicles, A Stranger at Green Knowe stands alone for its realism. There are no elusive ghost children from the time of the Great Plague, no malevolent witches, no time traveling stone chairs. There is just a boy and a gorilla.

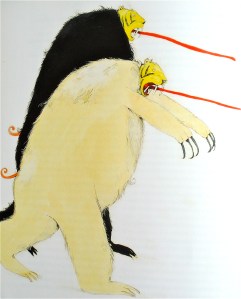

The extraordinary opening chapter stands at the pinnacle of atmospheric nature writing, and by itself justifies the award of the Carnegie Medal (the English equivalent of the Newbery Award). Written from the point of view of a young gorilla, it describes the rhythm of life of a gorilla family in the tropical forest of the Congo. Their world is abruptly shattered by a hunting party that kills the parents and captures the young male and his half-sister. Hanno, as he is named by his captors, ends up in a London zoo. The monkey house comes from an era of small square cages, concrete floors, and no attempted simulation of natural habitat – the only adornment is a small pile of straw.

The story picks up 11 years later when Ping, a Chinese refugee, visits the zoo with his fellow school children and feels an immediate affinity for the imprisoned gorilla, an awe-inspiring force of nature constrained behind bars. Their stories are analogous, for Ping’s childhood settlement in a Burmese forest was sacked and burned and his parents killed, and he himself has experienced the unyielding deadness of concrete in refugee camps. Ping goes to spend the summer holidays with the elderly Mrs. Oldknow at Green Knowe and Hanno, escaped from the zoo, finds refuge in a bamboo thicket on the estate. The boy surreptitiously aids the gorilla, secretly foraging for food in the vegetable garden, all the while anguishingly aware of the tightening noose of the pursuers.

The story picks up 11 years later when Ping, a Chinese refugee, visits the zoo with his fellow school children and feels an immediate affinity for the imprisoned gorilla, an awe-inspiring force of nature constrained behind bars. Their stories are analogous, for Ping’s childhood settlement in a Burmese forest was sacked and burned and his parents killed, and he himself has experienced the unyielding deadness of concrete in refugee camps. Ping goes to spend the summer holidays with the elderly Mrs. Oldknow at Green Knowe and Hanno, escaped from the zoo, finds refuge in a bamboo thicket on the estate. The boy surreptitiously aids the gorilla, secretly foraging for food in the vegetable garden, all the while anguishingly aware of the tightening noose of the pursuers.

Aside: “Here in their ugly, empty cages the monkeys were no more tropical than a collection of London rats or dirty park pigeons. They were degraded as in a slum. Some sat frowning with empty eyes, and those that wasted their unbelievable grace of movement, in leaping from perch to chain, from chain to roof, from roof to perch to chain, repeating it forever, had reduced to fidgety clockwork the limitless ballet of the trees, which is vital joy.”

Aside: For another tale of a gorilla in captivity, try The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2013 Newbery Award.

Aside: For another tale of a gorilla in captivity, try The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2013 Newbery Award.