The Story of Little Black Sambo by Helen Bannerman

1899

Illustrated by Helen Bannerman

Of the 100’s or 1000’s of picture books that a child is read in childhood, few make a permanent imprint. Enjoyed in the moment, they disappear like an Etch-a-Sketch picture when the book is closed. Every once in a while there is one that creates an indelible image and The Story of Little Black Sambo is one of these few. Read at the age of 3 or 5, many adults remember decades later the surreal scene of the tigers joined mouth to tail, whirling around the palm tree so fast that their bodies blur and they melt into butter. It is this remarkable scene that anchors the story in memory.

Helen Bannerman grew up in Madeira where she was home schooled, along with her six siblings, by her father, a minister who was more interested in the natural history of mollusks (his passion) than in his parishioners. After her marriage, she spent 30 years in India where her husband, a physician, devoted himself to combating bubonic plague. She wrote and illustrated The Story of Little Black Sambo for the amusement of her two young daughters, never imagining it for publication. Alice Boyd, a friend who was going on home leave, persuaded Bannerman to relinquish her manuscript. Unfortunately, Mrs. Boyd sold the copyright to a publisher for 5 pounds, contrary to Bannerman’s instructions, thus robbing the author of considerable financial rewards as well as control over subsequent editions.

The book was an immediate success in 1899 and continues to fascinate children a century later. The hero is a joyous character who combines bravery with artless ingenuity when confronted with four fierce tigers who are ultimately brought low by hubris. Bannerman wrote and drew with effortless simplicity, a quality that she applied to ten subsequent books. Her first remains her masterpiece.

The Story of Little Black Sambo is set in India and has Indian characters, but the illustrators of the many unauthorized editions often relocated the story to the American South or to Africa, sometimes with offensive caricatures in the picaninny or golliwog style. Accusations of racism in the 1960’s and 1970’s resulted in the book being banned from many libraries. Revised and rewritten editions appeared with renamed characters, altered locales, and self-consciously respectful images. Although these books were perhaps motivated by good intentions, they are singularly lacking. For the magic, seek out the original.

There is a certain randomness to outrage and censorship: take a look at Dr. Seuss’s If I Ran the Zoo or Jean de Brunhoff’s The Travels of Babar, both of which remain on library shelves with nary a whisper.

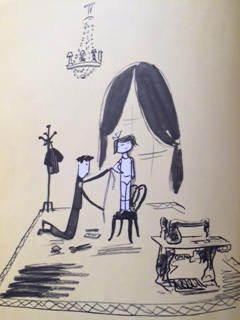

What is it about Madeline? Start with the opening. “In an old house in Paris/ that was covered with vines/ lived twelve little girls in two straight lines./…..the smallest one was Madeline.” Madeline emerges from the anonymous dozen in a defiant stance, posed like a statue on a dressmaker’s chair (the dressmaker on her knees) – clearly an individual. She distinguishes herself by being spirited and mischievous and fearless and independent, one in a rich canon of plucky heroines (going back to Jo in Little Women and Anne in Anne of Green Gables). Yet there is the reassuring predictability that attaches to being pa

What is it about Madeline? Start with the opening. “In an old house in Paris/ that was covered with vines/ lived twelve little girls in two straight lines./…..the smallest one was Madeline.” Madeline emerges from the anonymous dozen in a defiant stance, posed like a statue on a dressmaker’s chair (the dressmaker on her knees) – clearly an individual. She distinguishes herself by being spirited and mischievous and fearless and independent, one in a rich canon of plucky heroines (going back to Jo in Little Women and Anne in Anne of Green Gables). Yet there is the reassuring predictability that attaches to being pa rt of an identically dressed group, the comfort of daily identical routines, the safety provided by the watchful, albeit somewhat inept, care of Miss Clavel at a Paris boarding school, and the love conferred long-distance by a generous Papa.

rt of an identically dressed group, the comfort of daily identical routines, the safety provided by the watchful, albeit somewhat inept, care of Miss Clavel at a Paris boarding school, and the love conferred long-distance by a generous Papa. the night? There is a spirited joie de vivre that characterizes Bemelmans’ art, whether it be the iconic Parisian scenes that form the backdrop of the Madeline story or the humorous covers for the New Yorker or Town & Country. One has the sense of a life lived quickly and fully without slavery to detail. That Bemelmans once miscounted the dozen in his paintings or was not consistent with Madeline’s hair (which is variously blond, curly red, and black) adds to the charm.

the night? There is a spirited joie de vivre that characterizes Bemelmans’ art, whether it be the iconic Parisian scenes that form the backdrop of the Madeline story or the humorous covers for the New Yorker or Town & Country. One has the sense of a life lived quickly and fully without slavery to detail. That Bemelmans once miscounted the dozen in his paintings or was not consistent with Madeline’s hair (which is variously blond, curly red, and black) adds to the charm.