The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins by Dr. Seuss

1938

Illustrated by Dr. Seuss

Dr. Seuss achieved fame for his children’s books, but he had a lesser known career as a political cartoonist for a left-wing daily where he railed against fascism. His political views colored his books, most overtly in Yertle the Turtle, which features a despotic character inspired by Hitler. The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins has a more subtle message which has to do with the arrogance of power.

King Derwin looks down from his mountain-top palace over the castles, the mansions, and the houses to the distant farmer’s huts. Bartholomew, the unassuming son of a humble cranberry farmer, looks up over the houses, the mansions, and the castles to the palace. He has the same view as the King, only in reverse. As the King dashes through the town in his carriage, the townspeople hear the cry “Hats off to the King!” Bartholomew finds, to his dismay, that as quickly as he removes his hat, another appears on his head. The King calls in Sir Snipps, the royal hat maker, the three Wise Men, Yeoman the Bowman, seven magicians, and even the executioner – all to no avail. Finally, the nasty Grand Duke Wilfred, a boy himself, offers to push Bartholomew off a turret. As Bartholomew franticly sheds his hats as he climbs the stairs, they become increasingly ornate until the 500th has not only exotic bird plumes but a giant ruby. The King, delighted, offers 500 gold pieces for the hat and Bartholomew returns home, bareheaded at last.

Dr. Seuss began his career with And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street, a book that was rejected by 27 publishers. The title features the anapestic tetrameter rhythm that became one of his trademark meters. His second book, The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, was unusual (in retrospect) in that it was written in prose, as were the two subsequent Bartholomew books, The King’s Stilts and Bartholomew and the Oobleck. Without the distraction of the insistent rhymed beat, the prose trilogy is distinctive for the originality and strength of the stories. Intersperse these with the gentle Horton books and the standards (e.g., The Cat and the Hat) that celebrate the extravagance of the frenetic imagination. All have in common the unmistakable high-energy Seuss illustrations that combine frenzied motion, zany humor, and improbable beasts (or hats). The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins appears more subdued than some because it is in black and white, with only the red hats providing a splash of color.

We have, by the way, a college indiscretion (involving gin during the Prohibition era) to thank for Dr. Seuss’s pseudonym. Kicked off the Dartmouth humor magazine as punishment, Theodor Seuss Geisel adopted Dr. Seuss as a nom-de-plume so he could continue his submissions in disguise. Of German descent, he pronounced his name soice, rhymes with voice, until he was won over to the Americanized pronunciation, soose, which appropriately rhymes with Mother Goose.

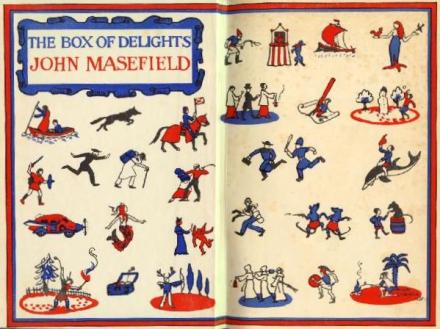

f Cape Horn, he landed in a Chilean hospital with sunstroke and a nervous breakdown before being deemed unfit and sent home. His aunt arranged for his next apprenticeship on a ship out of New York. Masefield failed to report for duty and, age 16, became a vagabond in America, determined to be a writer. The high point of his teen sailing years must have been the sighting of a lunar rainbow. Despite his traumatic experiences on ocean voyages, he is best known for his poems Sea-Fever (“I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky….”) and Cargoes (“Quinquereme of Ninevah from distant Ophir/ Rowing home to haven in Sunny Palestine.”) He was a prolific writer – of poems, novels, and plays – and was celebrated in the U.K. where he was Poet Laureate for almost forty years. Along the way, he

f Cape Horn, he landed in a Chilean hospital with sunstroke and a nervous breakdown before being deemed unfit and sent home. His aunt arranged for his next apprenticeship on a ship out of New York. Masefield failed to report for duty and, age 16, became a vagabond in America, determined to be a writer. The high point of his teen sailing years must have been the sighting of a lunar rainbow. Despite his traumatic experiences on ocean voyages, he is best known for his poems Sea-Fever (“I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky….”) and Cargoes (“Quinquereme of Ninevah from distant Ophir/ Rowing home to haven in Sunny Palestine.”) He was a prolific writer – of poems, novels, and plays – and was celebrated in the U.K. where he was Poet Laureate for almost forty years. Along the way, he

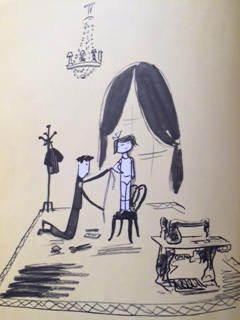

What is it about Madeline? Start with the opening. “In an old house in Paris/ that was covered with vines/ lived twelve little girls in two straight lines./…..the smallest one was Madeline.” Madeline emerges from the anonymous dozen in a defiant stance, posed like a statue on a dressmaker’s chair (the dressmaker on her knees) – clearly an individual. She distinguishes herself by being spirited and mischievous and fearless and independent, one in a rich canon of plucky heroines (going back to Jo in Little Women and Anne in Anne of Green Gables). Yet there is the reassuring predictability that attaches to being pa

What is it about Madeline? Start with the opening. “In an old house in Paris/ that was covered with vines/ lived twelve little girls in two straight lines./…..the smallest one was Madeline.” Madeline emerges from the anonymous dozen in a defiant stance, posed like a statue on a dressmaker’s chair (the dressmaker on her knees) – clearly an individual. She distinguishes herself by being spirited and mischievous and fearless and independent, one in a rich canon of plucky heroines (going back to Jo in Little Women and Anne in Anne of Green Gables). Yet there is the reassuring predictability that attaches to being pa rt of an identically dressed group, the comfort of daily identical routines, the safety provided by the watchful, albeit somewhat inept, care of Miss Clavel at a Paris boarding school, and the love conferred long-distance by a generous Papa.

rt of an identically dressed group, the comfort of daily identical routines, the safety provided by the watchful, albeit somewhat inept, care of Miss Clavel at a Paris boarding school, and the love conferred long-distance by a generous Papa. the night? There is a spirited joie de vivre that characterizes Bemelmans’ art, whether it be the iconic Parisian scenes that form the backdrop of the Madeline story or the humorous covers for the New Yorker or Town & Country. One has the sense of a life lived quickly and fully without slavery to detail. That Bemelmans once miscounted the dozen in his paintings or was not consistent with Madeline’s hair (which is variously blond, curly red, and black) adds to the charm.

the night? There is a spirited joie de vivre that characterizes Bemelmans’ art, whether it be the iconic Parisian scenes that form the backdrop of the Madeline story or the humorous covers for the New Yorker or Town & Country. One has the sense of a life lived quickly and fully without slavery to detail. That Bemelmans once miscounted the dozen in his paintings or was not consistent with Madeline’s hair (which is variously blond, curly red, and black) adds to the charm.