Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

1952

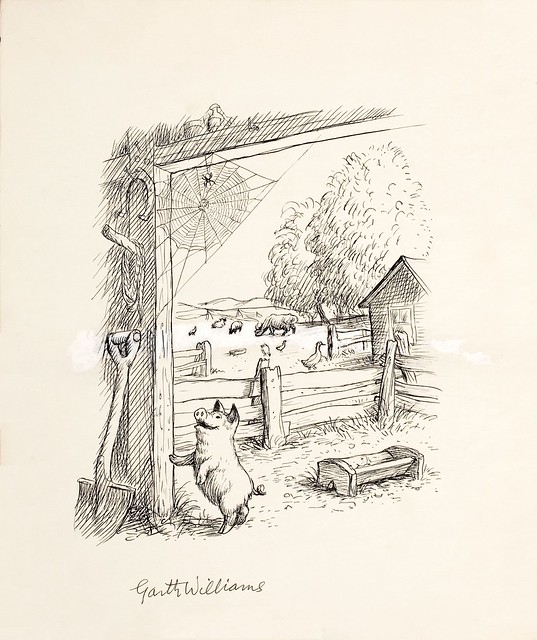

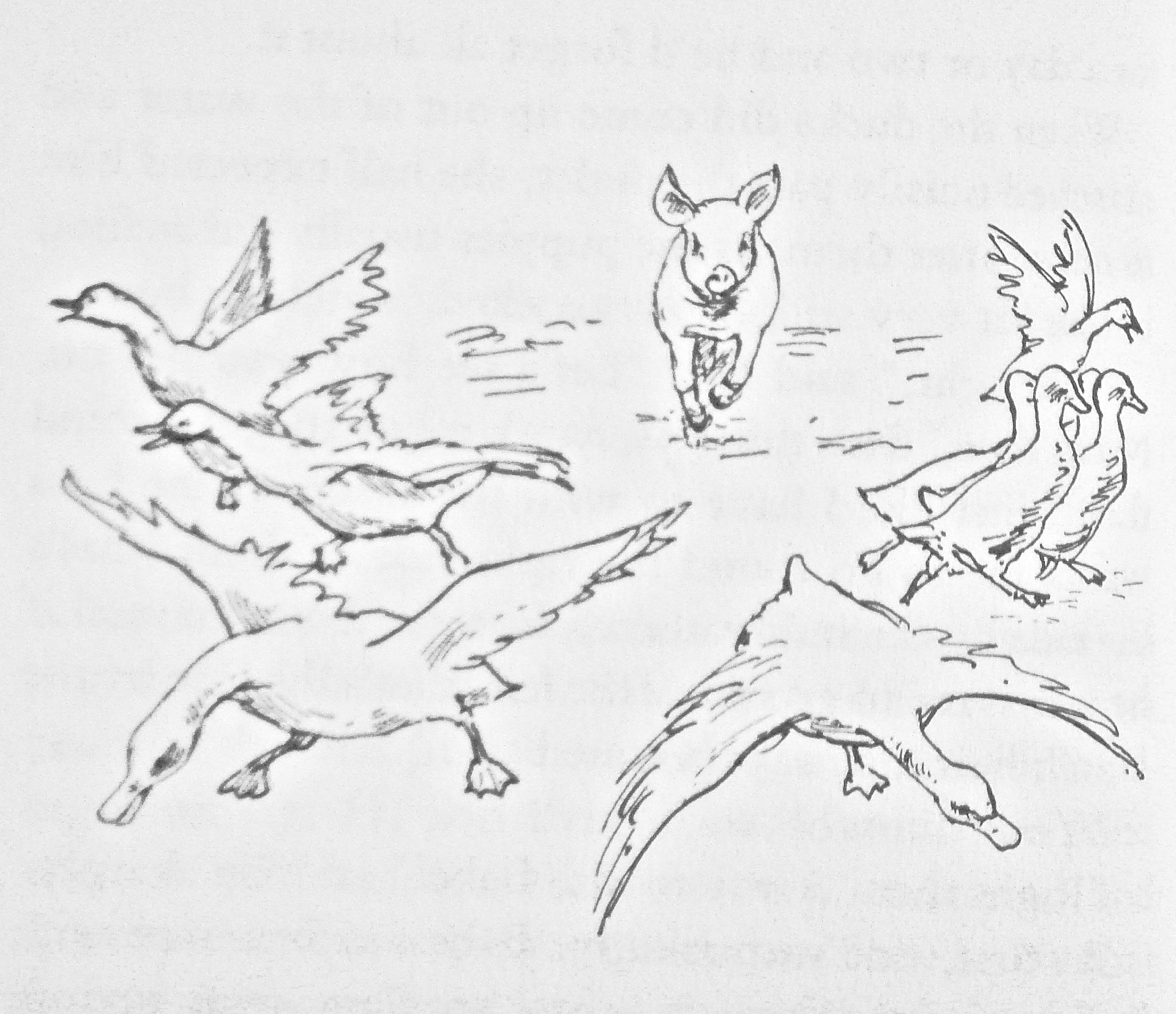

Illustrated by Garth Williams

E.B.White divided his time between New York City, where he wrote for the New Yorker, and a salt water farm in Maine, where he raised chickens, geese, sheep, and pigs. In 1948, he published an essay, “Death of a Pig”, in the Atlantic Monthly, which told a sad tale of his unsuccessful ministrations to a sick pig. He was unsettled by the irony of the scenario: his attempt to prevent the premature demise of a pig he was raising for eventual slaughter. He decided to write a children’s book about a pig who is saved from the seemingly inevitable butcher’s knife, and he eventually happened upon a barn spider as the instrument of salvation.

Charlotte’s Web is an intricate book that seamlessly interweaves the human story of Fern, an eight year old girl, with the animal story of young Wilbur, the pig, and Charlotte, the wise spider. Wilbur is saved by the carefully chosen words that his friend weaves into her web: SOME PIG, TERRIFIC, RADIANT, and HUMBLE. She is aided, sometimes accidentally, usually begrudgingly, by Templeton, the scurrilous rat, while the stuttering geese provide the comic chorus in the background.

Charlotte’s Web is arguably the best children’s book ever written. It has all the elements: a tight storyline that naturally overlays fantasy (talking animals and a writing spider) onto a lovingly depicted barnyard world, an assortment of nuanced and evolving characters, and an honest depiction of the loneliness of death while celebrating life, friendship, and the rhythm of nature. E.B. White was a consummate literary craftsman (he co-wrote The Elements of Style) and few have matched his ease and clarity of style, or his simple honesty.

E.B.White’s lack of pretence is apparent in his sound recording for the audiobook version of Charlotte’s Web. Dissatisfied with the reading by a professional actress, he chose to do a simple reading himself with his “famous monotone”. “I think a book is better read the way my father used to read books to me – without drama. He just read the words, beginning with the seductive phrase “Chapter One”, and I supplied my own dramatization.” He recorded the book, not in a sound studio, but in a friend’s living room, and he had to pause whenever a car drove by. He also recorded The Trumpet of the Swan, his third and final children’s book, and it is a pleasure to hear him read both stories.

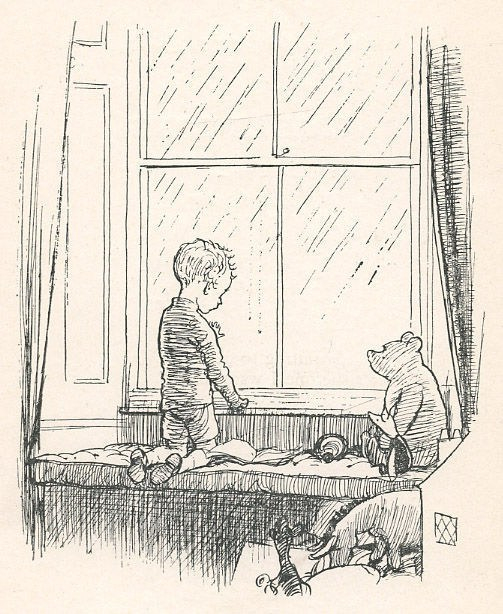

Aside: Garth Williams illustrated both Charlotte’s Web and the earlier Stuart Little. His early renditions of Charlotte featured a woman’s face. E.B.White, distressed, referred Williams to several arachnid natural histories. Fortunately, White prevailed.

Louisa was not without her share of sentimentality. One of her three sisters died at the age of 22. She had Beth, the fictional sister, follow suit. Beth, the impossibly kind, shy, selfless girl who Jo loves deeply. Her death would wring tears from a stone.

Louisa was not without her share of sentimentality. One of her three sisters died at the age of 22. She had Beth, the fictional sister, follow suit. Beth, the impossibly kind, shy, selfless girl who Jo loves deeply. Her death would wring tears from a stone.

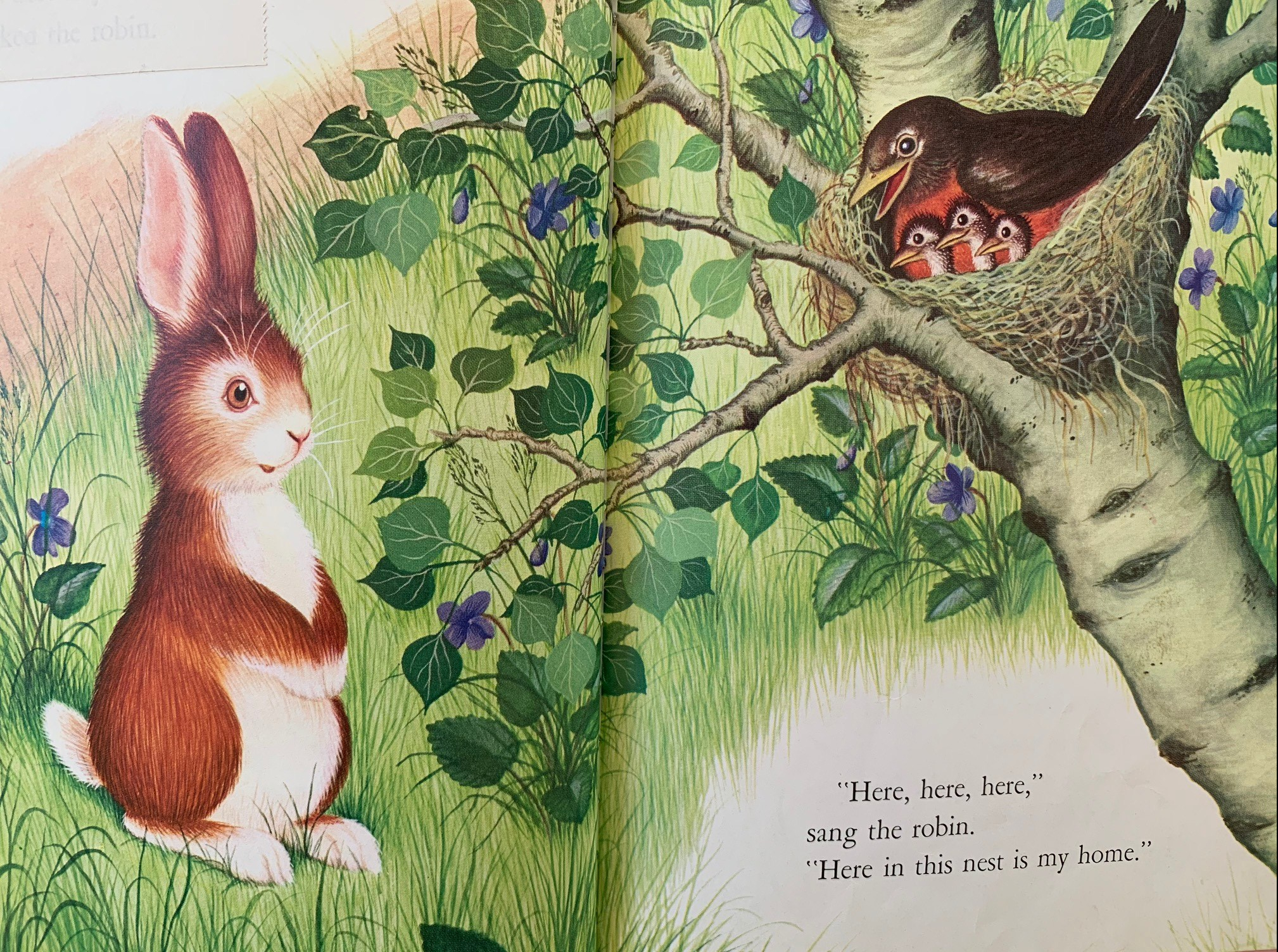

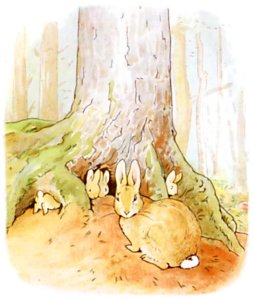

later people her stories. As a young adult, she developed a passionate interest in mycology and her botanical illustrations of fungi and lichens were highly regarded by other naturalists. In her children’s books, her illustrations of animal characters have become iconic, but her tree trunks, leaves, rocks, and dirt are as beautifully rendered as her velvety soft bunnies.

later people her stories. As a young adult, she developed a passionate interest in mycology and her botanical illustrations of fungi and lichens were highly regarded by other naturalists. In her children’s books, her illustrations of animal characters have become iconic, but her tree trunks, leaves, rocks, and dirt are as beautifully rendered as her velvety soft bunnies.

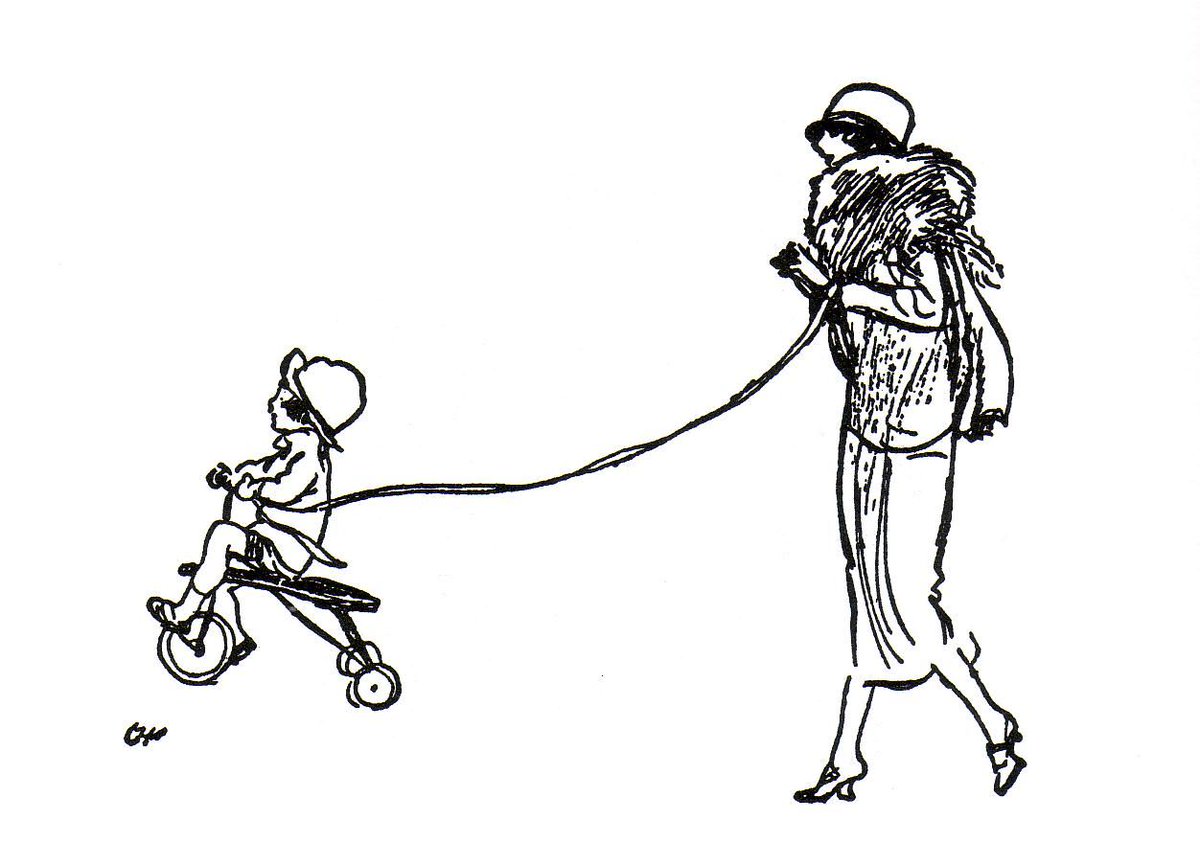

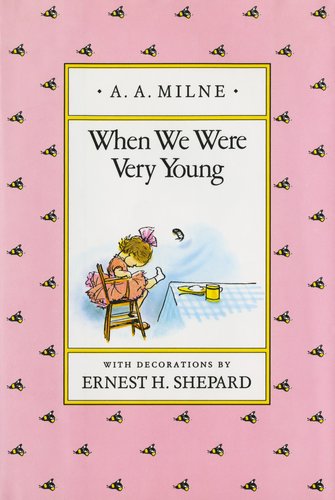

Disobedience is one of A.A. Milne’s most memorizable poems, and one of his best. He portrays the wonderful independence of a child’s mind and the natural audacity – James James goes immediately to the royals for help, in this case King John. Children reading the poem delight in the conceit – for children who are rarely in charge, it is a welcome relief to enter a world in which the mother is leashed to the tricycle rather than vice versa, and the mother is guilty of disobedience and suffers the consequences. It is a sign of Milne’s respect for children that there is no happy resolution – the mother is gone, for good. James James is not particularly sad about his loss, but simply disappointed that his mother failed to listen to him.

Disobedience is one of A.A. Milne’s most memorizable poems, and one of his best. He portrays the wonderful independence of a child’s mind and the natural audacity – James James goes immediately to the royals for help, in this case King John. Children reading the poem delight in the conceit – for children who are rarely in charge, it is a welcome relief to enter a world in which the mother is leashed to the tricycle rather than vice versa, and the mother is guilty of disobedience and suffers the consequences. It is a sign of Milne’s respect for children that there is no happy resolution – the mother is gone, for good. James James is not particularly sad about his loss, but simply disappointed that his mother failed to listen to him.